An Introduction to

THE BARD IN CALIFORNIA*

hat follows this introduction is an essay by Peter Fisher regarding a Zoomed Shakespeare series. I have known Peter nigh on half a century: he directed me in Under Milkwood and several other plays when we both lived in Pennsylvania; then he moved to Berkeley, California, and I, to New York City. In between long dry spells, we have somehow managed to stay in touch. My own theatre experiences became upstaged by my writing; but Peter continued, both as a flutist, a promoter of early music and, still, a theatre person. Recently, we've reconnected over the theme of "the Bard"; and it seems fit, as we leave Shakespeare's inspiration for the title of this journal for another, to pay tribute to him.

We have also—have we??—passed through the difficult times of the COVID epidemic; and many of us have reached out to one another virtually, perhaps far more than we would have otherwise. Zoom, presumably, is here to stay. I live out of country; and I for one, I admit, am glad for the opportunity Zoom gives me to stay in touch and/or reconnect with friends, family, and, dare I say?, my culture. Ah, the sound of the human voice! The sight, however distant, of another of my cohorts! In his essay, Peter makes a point about the act of reading Shakespeare aloud, as opposed to silently (and, presumably all by one's lonesome); and I am reminded of a recent BBC Radio 4 broadcast about, of all things, health, in which presenter Michael Mosley cites the fact that it has only been 400 years since we shifted to silent reading, "building worlds in our minds." Yes, many were illiterate before that time, and reading aloud was generally to a group gathered before the reader to listen.

Of course reading, period, is good for you: while reading aloud benefits your verbal memory even more than reading silently, reading fiction in particular has been demonstrated to benefit your verbal abilities (York University, Canada); and several studies have shown reading to benefit both your mental and physical heath (Yale University found that readers who read for a mere 30 minutes day lived almost two years longer than those who did not.)

But I digress. Fisher also queries, albeit a bit rhetorically, why the work of a dead white man? In a newsletter from no less than The Chronicle of Higher Education, Leo Gutkin references the "canon wars," now deeply inflected by our current "culture wars," and noting that he erroneously assumed that in 1st decade of the 21st century, "the canon wars had, if not gone away, at least cooled to a manageable simmer." Nope, "...but the last several years have seen a return to combat.":

As the sociologist of literature John Guillory wrote in Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon

Formation, back in 1993, “The canon debate will not go away, and it is likely to intensify as the positions of the

right and of the multiculturalists are further polarized.” Cultural Capital argued, convincingly to many, that

the reformers’ equation of symbolic representation with political representation obscured more than it

revealed.

As I have noted in my prelude essay on Ngugi in this issue, privileging one culture while diminishing another continues to have horrid consequences. However, just as using one's mother tongue for creative work necessitates an understanding of that language's music, it's linguistic subtleties and its impact thereof on other native speakers, knowing something about the prosody of rhyme-poor Anglo Saxon, about Elizabethan English and the language of the King James, the profound impact of African languages upon several Englishes—even, dear god!, of Latin—all this and more asks that we look at our old masters, warts and all, with both a critical and a necessary eye. Not as that by which all others should be measured, but just as Ngugi so clearly sees the richness of his orature, his culture's myth and tale-telling and performative traditions, as a necessary review and practise of our own—for better and for worse.

Indeed, I confess to having been an audience of one to both King John, Edward II, and King Lear, Part I. Despite the hats, the sonorous reading aloud, the Zoom virtual backgrounds chosen by some participants, the occasional recorder music played by some, none of the readings are a performance; rather they are a shared read among those, actors and non-, for the sheer love of the Bard's work; and, after my first listen, talking to Peter when that reading was done, the first words out of my mouth were, "Ah, language!"

Oh, and I might add, as I think of Ngugi's work that so brilliantly references the community aspect of Gikuyu (and other African) arts, yes, reading aloud at least was, tale-telling was, and in our world today live theatre IS, a communal activity. We share the experience with others, perhaps even feeling similar emotions, similar sensations simultaneously—so unlike sitting alone, peering at a "show" on our televisions, or streaming on our computers. And lord knows, the arts of the West, in particular, not only manifest, but outright suffer from the loss of, the diminishing sense of, community in its societies.

Viva Zoom Shakespeare!

hat follows this introduction is an essay by Peter Fisher regarding a Zoomed Shakespeare series. I have known Peter nigh on half a century: he directed me in Under Milkwood and several other plays when we both lived in Pennsylvania; then he moved to Berkeley, California, and I, to New York City. In between long dry spells, we have somehow managed to stay in touch. My own theatre experiences became upstaged by my writing; but Peter continued, both as a flutist, a promoter of early music and, still, a theatre person. Recently, we've reconnected over the theme of "the Bard"; and it seems fit, as we leave Shakespeare's inspiration for the title of this journal for another, to pay tribute to him.

We have also—have we??—passed through the difficult times of the COVID epidemic; and many of us have reached out to one another virtually, perhaps far more than we would have otherwise. Zoom, presumably, is here to stay. I live out of country; and I for one, I admit, am glad for the opportunity Zoom gives me to stay in touch and/or reconnect with friends, family, and, dare I say?, my culture. Ah, the sound of the human voice! The sight, however distant, of another of my cohorts! In his essay, Peter makes a point about the act of reading Shakespeare aloud, as opposed to silently (and, presumably all by one's lonesome); and I am reminded of a recent BBC Radio 4 broadcast about, of all things, health, in which presenter Michael Mosley cites the fact that it has only been 400 years since we shifted to silent reading, "building worlds in our minds." Yes, many were illiterate before that time, and reading aloud was generally to a group gathered before the reader to listen.

Of course reading, period, is good for you: while reading aloud benefits your verbal memory even more than reading silently, reading fiction in particular has been demonstrated to benefit your verbal abilities (York University, Canada); and several studies have shown reading to benefit both your mental and physical heath (Yale University found that readers who read for a mere 30 minutes day lived almost two years longer than those who did not.)

But I digress. Fisher also queries, albeit a bit rhetorically, why the work of a dead white man? In a newsletter from no less than The Chronicle of Higher Education, Leo Gutkin references the "canon wars," now deeply inflected by our current "culture wars," and noting that he erroneously assumed that in 1st decade of the 21st century, "the canon wars had, if not gone away, at least cooled to a manageable simmer." Nope, "...but the last several years have seen a return to combat.":

As the sociologist of literature John Guillory wrote in Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon

Formation, back in 1993, “The canon debate will not go away, and it is likely to intensify as the positions of the

right and of the multiculturalists are further polarized.” Cultural Capital argued, convincingly to many, that

the reformers’ equation of symbolic representation with political representation obscured more than it

revealed.

As I have noted in my prelude essay on Ngugi in this issue, privileging one culture while diminishing another continues to have horrid consequences. However, just as using one's mother tongue for creative work necessitates an understanding of that language's music, it's linguistic subtleties and its impact thereof on other native speakers, knowing something about the prosody of rhyme-poor Anglo Saxon, about Elizabethan English and the language of the King James, the profound impact of African languages upon several Englishes—even, dear god!, of Latin—all this and more asks that we look at our old masters, warts and all, with both a critical and a necessary eye. Not as that by which all others should be measured, but just as Ngugi so clearly sees the richness of his orature, his culture's myth and tale-telling and performative traditions, as a necessary review and practise of our own—for better and for worse.

Indeed, I confess to having been an audience of one to both King John, Edward II, and King Lear, Part I. Despite the hats, the sonorous reading aloud, the Zoom virtual backgrounds chosen by some participants, the occasional recorder music played by some, none of the readings are a performance; rather they are a shared read among those, actors and non-, for the sheer love of the Bard's work; and, after my first listen, talking to Peter when that reading was done, the first words out of my mouth were, "Ah, language!"

Oh, and I might add, as I think of Ngugi's work that so brilliantly references the community aspect of Gikuyu (and other African) arts, yes, reading aloud at least was, tale-telling was, and in our world today live theatre IS, a communal activity. We share the experience with others, perhaps even feeling similar emotions, similar sensations simultaneously—so unlike sitting alone, peering at a "show" on our televisions, or streaming on our computers. And lord knows, the arts of the West, in particular, not only manifest, but outright suffer from the loss of, the diminishing sense of, community in its societies.

Viva Zoom Shakespeare!

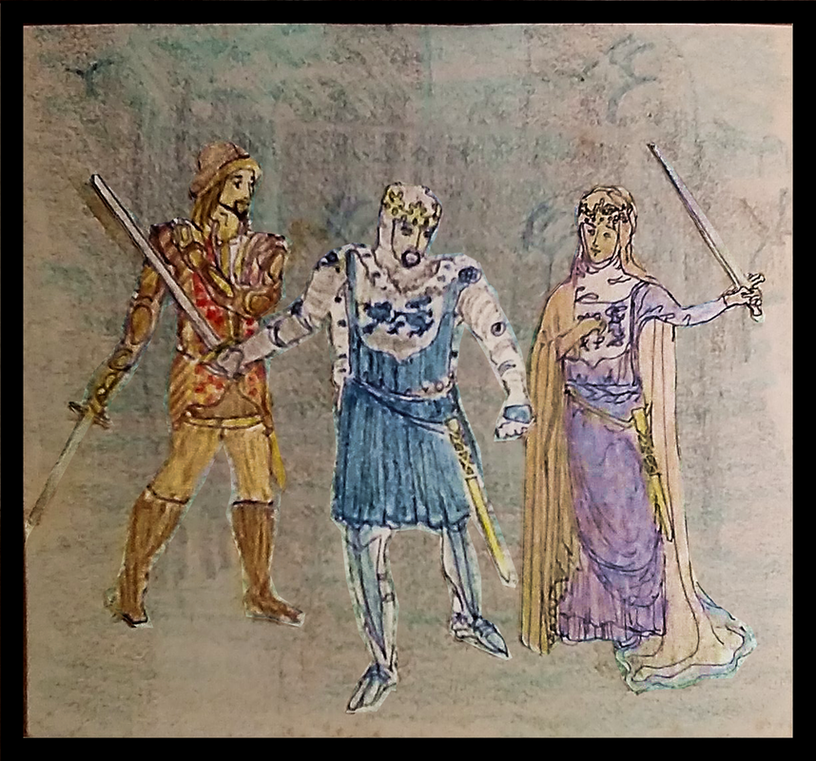

*My thanks to Stanley Spenger and Mardi Sicular for relevant conversations about their experiences with the Bard, and to Stan for his wonderful illustrations.