Ngugi wa Thiong'o in the American Imperium

|

Here follows a brief prelude to a longer consideration of the important contribution made by Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Kenyan born writer, to literature locally and globally. Most recently, Ngugi (once James Ngugi when writing his first novels in English as opposed to his now writing in Gikuyu, his mother tongue), Ngugi was awarded the 2022 PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature. Several times, he has been on the short list for the Nobel—the list of his kudos is long. At University of California Irvine he became the first Director of the ICWT, Irvine Center for Writing and Translation as well as Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature in its School of Humanities.

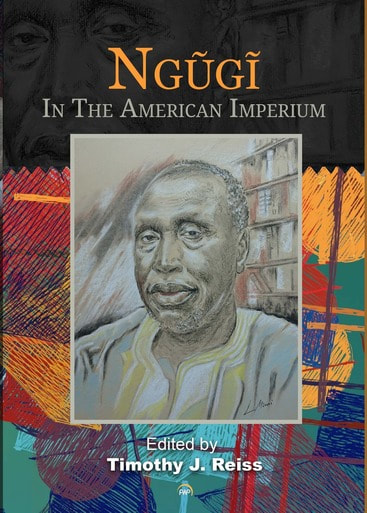

In this prelude, I will focus, loosely, on Ngugi in the American Imperium, ed. Tim Reiss, which offers a collection of essays from both academics, writers, and other luminaries on Ngugi and his project during his long exile in the United States. As we move from Witty Partition to our new name, Cable Street, readers will find a much more ample treatment of the same subject, though that excellent volume may serve as a touchstone. |

|

I am no longer in academia, and it is a bit daunting to write about one's former teacher, esp. when I, as do many others, when I hold him is such high esteem. Nonetheless, adelante!

Indeed, I still receive emails from MLA, asking me to pay to rejoin, as well as The Chronicle of Higher Education, also asking me to, yes, pay and resubscribe; and I receive a free Chronicle of Higher Education newsletter. Most recently the newsletter begins with a brief essay or commentary by Len Gutkin on a topic of intellectual concern. Gutkin's writing is gratefully absent of "academic speak" and often interesting. In the beginning of June, in the second of his brief series on the "Canon wars,"* he commented on the '90s campaign to stop a Library of Congress exhibition, "Sigmund Freud: Conflict and Culture” which nearly cancelled the exhibit, but apparently postponed it for several years. Objection appears to have been largely centered on the way Freud painted human sexuality—with, shall we |

say, a rather broad brush—and Gutkin went on to talk about various art and museum exhibitions which have suffered from minor to major elements of, for lack of a better term, political incorrectness. Suggested in Gutkin's essay/introduction to another more ample one on the subject is the lack of critical acuity employed, both on the part of all too many viewers and on the part of museums, etc., wanting to warn visitors, oh so unctuously and carefully, that dubious elements exist. The latter, he says, sounds 'silly' (I am tempted to say 'fluffy') and does not address genuine concerns, whereas the former may have very good reason to object to subjects that are overtly racist, mysogynist, sexist, and so forth.

But there is a point here. How does one sift through this standoff among legitimate concern, 'Wokeness' and the downright fascistic leanings so increasingly evident in the body politic today? In his Moving the Centre, a collection of talks and essays given between 1985-1990, originally written in Gikuyu and translated by the author, Ngugi's first chapter, "Moving the Center: Towards a Pluralism of Cultures," under the rubric of his first section, "Freeing Culture from Eurocentrism," Thiong'o speaks of the work of Joseph Conrad, who was "...Polish, born in a country and a family which had known only the pleasures of domination and exile....He had learned English late in life and yet he had chosen to write in it, despite his fluency in his native tongue and in French."(5) Conrad's work, Ngugi wrote, clearly focussed on imperialism; and, further, Conrad had also "chosen allegiance to the the empire and the moral ambivalance in his attitude towards British imperialism stems from that chosen allegiance." (6) Conrad, thus, situated himself in a Western-oriented "centre" whereas the centre that Ngugi wants to shift to would include and acknowledge the value of the literary work of the postcolonial world. [Or, as his more recent work, cited by Reiss, Secure the Base (2016), puts it, to give equal value to the local and the global.]

Might one speculate, vis à vis Ngugi's comments about Conrad, that Conrad's mind had been colonized by imperialist Britain's English?** I leave a fuller discussion of that process for another time; but here emerges an important and wider consideration for which Ngugi has become known, that of language, the imposition of Western imperialist languages as "colonizing the mind," versus, in part, a response to the question, who is your audience/ reader? By 1977 Ngugi was already writing in his mother tongue, Gikuyu, continuing most famously when in prison in his first novel in Gikuyu, Caitaani mutharaba-Ini, or, as translated into English, Devil on the Cross (1980.) In Centre he has argued for the teaching of literature that maintains the integrity of mother tongue while at the same time using translation where needed (and, in fact, looking at translations as legitimate text for study), and exposing students "to all streams of the human imagination flowing from all the centres in the world."(11)

Here we have the dilemma of considering work and influences that offer both admirable aesthetics, but have, to put it coloquially, clay feet. I do not mean that other variation, what I call "the Ezra Pound problem"; i.e., admirable work emanating from a very dubious, if not downright nasty, character. Rather I am thinking of the problems touching upon the pros and cons of extolling "The Canon"—inevitably the asserted great works of colonizing powers— in favor of a genuinely inclusive and nuanced approach to, and respect for, the cultures of post -colonial peoples as well as an invigorated critique of those elements in canonical work that offend. For those who teach must fortify the critical capacity of students, not to avoid, but look squarely at failings in work imposed as the measure of all things literary, so as to both understand and resist its offenses.

In Ngugi and the American Imperium, this dilemma of course presages a discussion about Ngugi wa Thiong'o, his work and ideas. Indeed, "...even Freud" as Reiss puts it, is offered as one of Ngugi's "natural interlocutors" in Simon Gikandi's contribution to the book, "Imagining Capital: Ngũgĩ, Marx and Freud." Gikandi states, "We know of course, that capitalism and the novel were made for each other"; and he perceives "a 'Freudian' unconsciousness seeping into 'Marxist' consciousness." Further, in his consideration of Freud, Gikandi, regards Ngũgĩ's attempts to decolonize the novel as "a creative problem...[despite the argument that]...Freud's unconscious is often said to apply not to people universally but to a specific group of bourgeoise Europeans...."(15)

Without refocussing on the details of Gikandi's interesting essay, the question which comes to mind, is how definitive is one thinker's idea of the human psyche's processes? Is Freud's "subconcious" the ultimate definition of notions of sub- or un-consciousness? Are we succumbing to the seductions of one, admittedly Eurocentric intellectual's, idea of the workings of the human mind? Using that only, rather than another's? Or, let's just face it: yes, Freud's work is of the Western European mind, not everyone's. Look at it for what it is, understand where it veers off course and harms rather than helps, and don't be afraid to look at the work to understand its influence, failings and, perhaps, its helpful suggestions.

Back to literature, with one more note from Simon Gikandi's contribution to Ngugi and the American Imperium. Gikandi briefly cites via Ian Watt's the Rise of the Novel (1957!) where capitalism and the novel "is an invitation to reflect...on the power of new social systems pegged on commodities...." and where individualism and the individuals are "agents of social transformation" (29-30), not the community. As Ngugi's fiction appears in the form of the novel, this goes on to raise an interesting question: is the novel as a literary form, ipso facto, always incarcerated in a colonizer's bourgeoise sensibility? In the bonds of capitalism and its commodification of (seemingly) just about everything? I remember Ngugi's own comment, regarding his decision to write in Gikuyu, his mother tongue, when incarcerated by Kenyan then-dictator Jomo Kenyatta via his home minister, Daniel Arap Moi, who later became Kenya's second president, and I paraphrase: I was trying to think, given our rich orature—oral culture and traditions—how would you write a novel in Gikuyu? It would have to be different. What Reiss points out, in introducing the collection and as Christopher Wink's contribution offers, Ngugi's work is "...essential to the necessary task to change society from economistic capitalist, imperialist, colonial and class oppressions and alienation to ecological forms of global and local community/ies that incorporate all people(s).(16) Reiss further refers to Ngugi's novels as "decolonizing 'instruments'" which have profoundly affected writers as well as those in other disciplines. (ibid)

I think back to my own obsessions: the bizarre vacuity of so many Northamerican contemporary novels with protagonists incarcerated in a bourgeoise prison of "personal" relationships, thinly disguised authors compelled to narrate their own empty lives...and so on. Are the prison walls that of class as well? Of a class bereft of community? Clearly, as individualism and its attendant narcissism runs rampant, capitalism itself has colonized their minds.

What I would repeat here is what, to this writer at least, Ngugi's thoughts that I paraphrased about writing in Gikuyu presuppose, instinctively, that orature and its traditions emerge from community and are communal, whereas, alas, the so-called colonizing Western author's, from "social systems pegged on commodities" in which that author is a lone voice reflecting back the values of the Imperium. In contrast, it is no accident that he has in his latest, The Perfect Nine, reconstructed a founding myth of the Gikuyu which automatically assumes an audience of people, not a single reader going off, book in hand—pardon the analogy—like a dog going off to hide a bone.

Ngugi has observed that nations, who themselves strongly protect and wall out "others," "...those who might threaten a nation's economic or intellectual or whatever capital, are effectively prisons." (The current UK government's offensive, illegal, and downright cruel variation—criminalizing, making prisoners of, asylum seekers that arrive on their shores and shipping them from Prison UK to Prison Rwanda comes to mind.) Indeed, the notion of walls is not a simple idea to unpack. As Ngũgĩ's Secure the Base has noted, the European nation state, the slave plantation, the colony, and the prison were all the "simultaneous products of the same moment in history." (45) Thus, we are left with a dilemma: I, for one, would happily dance around the funeral pyre of Mein Kampf, "replacement theory" and other such obscenities; but the more, in a sense, subtle bourgeoise obsession with individual psychic angst,

[anti-]social media, adolescent biographies that separate rather than include, implicit assertions of economic and social privilege, and even the Thanksgiving basket mentality posing as knee-jerk politial correctness, woke-ness, whatever you want to call it--these persist in far too many contemporary novels without being seriously considered challenged, artistically or intellectually. Ngugi's project offers a more humane, artistic alternative. (To be continued.)

But there is a point here. How does one sift through this standoff among legitimate concern, 'Wokeness' and the downright fascistic leanings so increasingly evident in the body politic today? In his Moving the Centre, a collection of talks and essays given between 1985-1990, originally written in Gikuyu and translated by the author, Ngugi's first chapter, "Moving the Center: Towards a Pluralism of Cultures," under the rubric of his first section, "Freeing Culture from Eurocentrism," Thiong'o speaks of the work of Joseph Conrad, who was "...Polish, born in a country and a family which had known only the pleasures of domination and exile....He had learned English late in life and yet he had chosen to write in it, despite his fluency in his native tongue and in French."(5) Conrad's work, Ngugi wrote, clearly focussed on imperialism; and, further, Conrad had also "chosen allegiance to the the empire and the moral ambivalance in his attitude towards British imperialism stems from that chosen allegiance." (6) Conrad, thus, situated himself in a Western-oriented "centre" whereas the centre that Ngugi wants to shift to would include and acknowledge the value of the literary work of the postcolonial world. [Or, as his more recent work, cited by Reiss, Secure the Base (2016), puts it, to give equal value to the local and the global.]

Might one speculate, vis à vis Ngugi's comments about Conrad, that Conrad's mind had been colonized by imperialist Britain's English?** I leave a fuller discussion of that process for another time; but here emerges an important and wider consideration for which Ngugi has become known, that of language, the imposition of Western imperialist languages as "colonizing the mind," versus, in part, a response to the question, who is your audience/ reader? By 1977 Ngugi was already writing in his mother tongue, Gikuyu, continuing most famously when in prison in his first novel in Gikuyu, Caitaani mutharaba-Ini, or, as translated into English, Devil on the Cross (1980.) In Centre he has argued for the teaching of literature that maintains the integrity of mother tongue while at the same time using translation where needed (and, in fact, looking at translations as legitimate text for study), and exposing students "to all streams of the human imagination flowing from all the centres in the world."(11)

Here we have the dilemma of considering work and influences that offer both admirable aesthetics, but have, to put it coloquially, clay feet. I do not mean that other variation, what I call "the Ezra Pound problem"; i.e., admirable work emanating from a very dubious, if not downright nasty, character. Rather I am thinking of the problems touching upon the pros and cons of extolling "The Canon"—inevitably the asserted great works of colonizing powers— in favor of a genuinely inclusive and nuanced approach to, and respect for, the cultures of post -colonial peoples as well as an invigorated critique of those elements in canonical work that offend. For those who teach must fortify the critical capacity of students, not to avoid, but look squarely at failings in work imposed as the measure of all things literary, so as to both understand and resist its offenses.

In Ngugi and the American Imperium, this dilemma of course presages a discussion about Ngugi wa Thiong'o, his work and ideas. Indeed, "...even Freud" as Reiss puts it, is offered as one of Ngugi's "natural interlocutors" in Simon Gikandi's contribution to the book, "Imagining Capital: Ngũgĩ, Marx and Freud." Gikandi states, "We know of course, that capitalism and the novel were made for each other"; and he perceives "a 'Freudian' unconsciousness seeping into 'Marxist' consciousness." Further, in his consideration of Freud, Gikandi, regards Ngũgĩ's attempts to decolonize the novel as "a creative problem...[despite the argument that]...Freud's unconscious is often said to apply not to people universally but to a specific group of bourgeoise Europeans...."(15)

Without refocussing on the details of Gikandi's interesting essay, the question which comes to mind, is how definitive is one thinker's idea of the human psyche's processes? Is Freud's "subconcious" the ultimate definition of notions of sub- or un-consciousness? Are we succumbing to the seductions of one, admittedly Eurocentric intellectual's, idea of the workings of the human mind? Using that only, rather than another's? Or, let's just face it: yes, Freud's work is of the Western European mind, not everyone's. Look at it for what it is, understand where it veers off course and harms rather than helps, and don't be afraid to look at the work to understand its influence, failings and, perhaps, its helpful suggestions.

Back to literature, with one more note from Simon Gikandi's contribution to Ngugi and the American Imperium. Gikandi briefly cites via Ian Watt's the Rise of the Novel (1957!) where capitalism and the novel "is an invitation to reflect...on the power of new social systems pegged on commodities...." and where individualism and the individuals are "agents of social transformation" (29-30), not the community. As Ngugi's fiction appears in the form of the novel, this goes on to raise an interesting question: is the novel as a literary form, ipso facto, always incarcerated in a colonizer's bourgeoise sensibility? In the bonds of capitalism and its commodification of (seemingly) just about everything? I remember Ngugi's own comment, regarding his decision to write in Gikuyu, his mother tongue, when incarcerated by Kenyan then-dictator Jomo Kenyatta via his home minister, Daniel Arap Moi, who later became Kenya's second president, and I paraphrase: I was trying to think, given our rich orature—oral culture and traditions—how would you write a novel in Gikuyu? It would have to be different. What Reiss points out, in introducing the collection and as Christopher Wink's contribution offers, Ngugi's work is "...essential to the necessary task to change society from economistic capitalist, imperialist, colonial and class oppressions and alienation to ecological forms of global and local community/ies that incorporate all people(s).(16) Reiss further refers to Ngugi's novels as "decolonizing 'instruments'" which have profoundly affected writers as well as those in other disciplines. (ibid)

I think back to my own obsessions: the bizarre vacuity of so many Northamerican contemporary novels with protagonists incarcerated in a bourgeoise prison of "personal" relationships, thinly disguised authors compelled to narrate their own empty lives...and so on. Are the prison walls that of class as well? Of a class bereft of community? Clearly, as individualism and its attendant narcissism runs rampant, capitalism itself has colonized their minds.

What I would repeat here is what, to this writer at least, Ngugi's thoughts that I paraphrased about writing in Gikuyu presuppose, instinctively, that orature and its traditions emerge from community and are communal, whereas, alas, the so-called colonizing Western author's, from "social systems pegged on commodities" in which that author is a lone voice reflecting back the values of the Imperium. In contrast, it is no accident that he has in his latest, The Perfect Nine, reconstructed a founding myth of the Gikuyu which automatically assumes an audience of people, not a single reader going off, book in hand—pardon the analogy—like a dog going off to hide a bone.

Ngugi has observed that nations, who themselves strongly protect and wall out "others," "...those who might threaten a nation's economic or intellectual or whatever capital, are effectively prisons." (The current UK government's offensive, illegal, and downright cruel variation—criminalizing, making prisoners of, asylum seekers that arrive on their shores and shipping them from Prison UK to Prison Rwanda comes to mind.) Indeed, the notion of walls is not a simple idea to unpack. As Ngũgĩ's Secure the Base has noted, the European nation state, the slave plantation, the colony, and the prison were all the "simultaneous products of the same moment in history." (45) Thus, we are left with a dilemma: I, for one, would happily dance around the funeral pyre of Mein Kampf, "replacement theory" and other such obscenities; but the more, in a sense, subtle bourgeoise obsession with individual psychic angst,

[anti-]social media, adolescent biographies that separate rather than include, implicit assertions of economic and social privilege, and even the Thanksgiving basket mentality posing as knee-jerk politial correctness, woke-ness, whatever you want to call it--these persist in far too many contemporary novels without being seriously considered challenged, artistically or intellectually. Ngugi's project offers a more humane, artistic alternative. (To be continued.)

* Precursor, he suggests, to the "culture wars," and other such movements issuing from it.

**And, in 1917, Reiss points out, Ngugi stressed Conrad's "...art and his globalectic sense of writing, music and aesthetics."(Imperium, 5)

**And, in 1917, Reiss points out, Ngugi stressed Conrad's "...art and his globalectic sense of writing, music and aesthetics."(Imperium, 5)

Books cited:

Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms.

James Currey, London. EAEP Nairobi, Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H. (1993,

Devil on the Cross, Trans. by the author. Heinemann (1987). First published in

Gikuyu, (1980).

Secure the Base: Making Africa Visible in the Globe. Seagull Books, (2016).

Ngugi in the American Imperium, Reiss, Timothy, ed. Africa World Press (2021).

Ian. The Rise of the Novel. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles (1957).

Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms.

James Currey, London. EAEP Nairobi, Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H. (1993,

Devil on the Cross, Trans. by the author. Heinemann (1987). First published in

Gikuyu, (1980).

Secure the Base: Making Africa Visible in the Globe. Seagull Books, (2016).

Ngugi in the American Imperium, Reiss, Timothy, ed. Africa World Press (2021).

Ian. The Rise of the Novel. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles (1957).