Cheb Khaled & The Politics of Pleasure (1994)

Brian Cullman

|

Whenever things would get too quiet backstage, the dwarf would start to dance. It was a harsh, unlovely dance, frightening in its power and disdain; his large head thrown back, eyes narrowed to slits, tongue hanging out of his pink, wet mouth, the tiny body surged and gyrated in a mockery of a belly-dancer's dark and passionate rhythms, his hands describing small concentric circles in the air.

On the couch, Cheb Khaled sat drinking and laughing, checking his watch to see how long before the concert hall would clear so that we could unload and head back to the hotel; scattered about the room, half a dozen band members ignored the dwarf and went about packing their instruments, changing their shirts, and kibbitzing about the night’s show. Someone picked up a clay drum from the corner and began playing along to the dance, working up a slow, Arabic groove. The dwarf stopped, kicked the drum viciously, upsetting a tray of beers, and spat on the floor. “Turds,” he sneered. “Assholes. Musicians.” The last insult delivered with an air of unspeakable contempt and finality. There was a knock, and a man with a raincoat, a pencil-thin moustache, and the saddest expression in the world entered the room. “I'm not supposed to be here. I talked my way in,” he said to no one in particular and then turned his attention to Khaled. “You,” he said. “I knew you in Oran when you were a boy. And now I’m going to kill you.” Reaching into his coat, he pulled out a bottle of J&B scotch, Khaled’s drink of choice. “Back in Algeria, we were always getting into trouble,” he mused, nodding at Khaled, but addressing his whiskey.” One time, we’d been up for three, maybe four days, drinking and carousing and carrying on, breaking windows, whatever. Up to no good. “Finally,” he shrugged, pulling on his moustache,” we were arrested. What else could they do? But when the chief of police saw Khaled being led into court in handcuffs, he was furious; he leaped over the desk and knocked the arresting officer down to the ground and let us go. He even told Khaled that it was okay, he could kick the policeman if he wanted to, if it would make him feel better.” Did he? “Khaled? No, no, he’s a poet, he wants peace and happiness, he wouldn’t do something like that. But me…” he shrugged,” me, I’m not so nice. ***

The next night, driving back to Paris from Barcelona, I ask Khaled about the story.

“Yes, of course,” Khaled shrugs, as if stating the obvious. “But that was a long time ago. Anyway, that’s not the funny part.” The funny part? “Yes, you know that skinny guy you were talking to? He’s a good friend and a big fan of rai, that and whiskey, they’re everything to him. Anyway, he’s in jail someplace in Algeria, for what, I don’t know, there’s always something. Whenever he hears that I’m playing a concert somewhere in Spain, he breaks out of jail and sneaks across the border, he doesn’t have a passport, of course, he’s not that type, hitchhikes to the town I’m playing in and talks his way in. He hears the music, we drink a few bottles, and the next day he sneaks back across the border, gives himself up and goes back to jail. “Only last night, he got the times wrong. He broke out of jail, came all the way to Barcelona, and he missed the whole fucking show!” Khaled throws his head back and laughs, beating his hands against the steering wheel and speeding up. We’re already going 180 kilometres an hour; accelerating, it feels like we’re driving straight into the night sky. ***

This is the world of rai, the Algerian music that has swept North Africa, the Middle East and Europe, bypassing America altogether (but for a few urban pockets). With its surging rhythms, melding the sultry trance feel of Oriental belly dance with Latin trumpet, the electronic pulse of hiphop, and funky, propulsive bass lines, rai may be the most exciting music being made on the planet right now and is the first international sound to develop and take hold since the emergence of reggae over forty years ago. With wars, emigration, and a constantly declining infant mortality rate creating a population curve, over 60% of the people in North Africa and in much of the Middle East are under 25 years of age, and rai is their beat, their music, the sound of young Islam getting down to a serious groove. And Cheb (or young) Khaled, the charismatic architect of modern rai, is their Elvis, their Beatles and their Sex Pistols rolled into one.

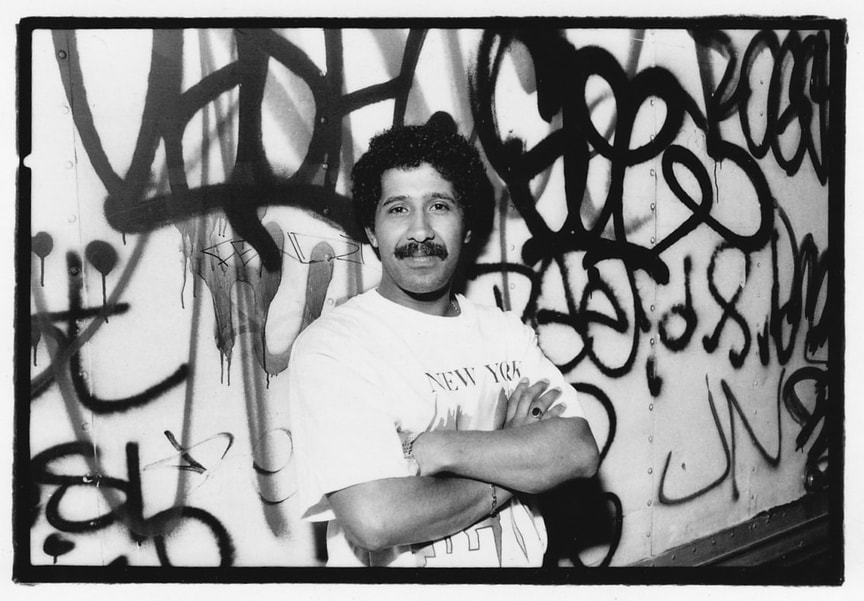

“I traveled all through the Middle East earlier this year,” said Martin Meissonier, the French entrepreneur who co-produced Kutche, Khaled’s last release,” and everywhere I went, Khaled was number one, the most popular album in Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Syria. Of course,” he sighs, ”it was never actually released in any of those countries.” Not very long ago, in Algeria’s port town of Oran, a man driving through town in a convertible, listening to a tape of Khaled, was dragged out of his car and beaten to death by fundamentalists. Small wonder Khaled has made his home in Marseilles for the last five years, where, among France’s 3 to 4 million resident Arabs, he is regarded as a king in exile. Khaled seems an unlikely figure to have caused so much trouble and stirred so much anger. Saddled with a reputation as rai’s bad boy and known for his excesses with alcohol and women, Khaled comes across as neither a brooding rebel nor a spoiled pop star, but as that rarest of commodities, a genuinely happy man on whom both talent and fortune have smiled. With dark good looks, almond eyes, and thick black hair and moustache, he resembles a handsome Richard Pryor, with a mouth that is sensual and slightly over-indulged, but saved by a warm and easy smile. In performance, it’s the laugh you notice first, and it’s no accident that all of his concert posters show him laughing, head thrown back in absolute abandon. Surrounded by his band onstage, he seems oblivious to everything but the music; he sings and is clearly delighted by the sound of his own voice (a rich, unmistakable baritone that mixes the wail of a muezzin’s call to prayer with the sassy bravado of L’il Wayne or Wilson Pickett); by the arc of the melody; and by the way the sound swirls around him in spirals of interconnecting rhythms. He stands there locked inside a happiness as serious as a child’s, as if pleasure itself were a prayer, and this were the only way to heaven. In concert, Khaled seems like a character from “The 1001 Nights,” an ordinary man who, through chance or luck or by catching an enchanted fish, has suddenly and inexplicably been made king or vizier… and who just as inexplicably turns out to be a splendid ruler. In front of his six piece band, a crack outfit that seems able to read his every gesture, Khaled looks uncontrollably happy, as if he can’t believe his good fortune in having this band and this audience, in being able to live this moment. He watches the band proudly: the drummer and percussionist trade patterns, creating a circular rhythm; the bass and guitar player groove, finding a place somewhere between reggae and latin funk; the keyboard keens a high, Oriental melody; and the trumpet player fills in the spaces, a tiny red sportscar weaving in and out of traffic. And then he starts to sing, and the band members take turns grinning at each other, shaking their heads, digging just a little deeper into the beat. Those are the sort of looks people in Jimi Hendrix’s band or Charlie Parker’s group must have exchanged when Hendrix or Parker started to play, and the heavens opened up. You know the look or you can imagine it, the look that says, ”We’re here, we’ve found it, that place at the center of the world, that tick at the center of the clock. We’re fucking here!” And of course they’re right. ***

The word rai means “opinion” in Arabic, and like Greek rembetika music or American blues, country or rap, it’s always been based on a straight talking look at life as it’s actually lived, detailing in raw and graphic terms the pain and humiliation of the daily grind while acknowledging the occasional consolations of whiskey and sex.

“In rai, you sing your true feelings,”says Khaled. “The lyrics come straight from your life, from your heart. It’s about real life, not life as it’s supposed to be or as it’s shown on tv.” “There is a certain roughness to rai, the same as there’s a roughness to blues,” explains Cheb Sahroui, a singer and composer, who, with his wife Chaba Fadela, has recorded some of rai’s most successful songs. “In someways it’s a reaction to all of the flowery Arabic songs we grew up with, all the flowers in the misty pool and the young gazelle whose heart quickens in the forest of night. I’ve never seen a gazelle, have you? That’s not what our lives are about, those of us who live in cities, those of us who’ve come to Paris or Marseilles looking for more out of life. “Rai is about our past as well as our present, it’s where we come from as well as where we think we’re going. It’s about love and money and security. And it’s about their absence, their lack. “I remember a session from a few years ago in Oran, where a singer came in to record a new song. The producer started the tape, and the singer began this really passionate, really gritty piece… something like: Late tonight / when the moon is full and golden / I will fuck you on the floor / of the dirtiest hotel in town / and the moon will shine on your ass. And the producer went STOP! You can’t sing that! You have to tone this down or no one will ever play the record. So the singer took a walk for an hour or so, had a drink, and when he came back, he said, I know how to fix it, no problem, start the tape. And he sang: Late tonight /when the moon is full and golden / I will fuck you on the floor / of the most expensive hotel in town. ***

“Rai really started in the 1920’s in Oran,” Khaled explains. “The music in the rest of Algeria and in Morocco was different; being a port, Oran had the most nightclubs and bars and bordellos, and it had the most trade, the most travel. The city was open to a real mix of cultures: Spanish, French, Moroccan, even American, and that mix found its way into the music.”

Accompanied by darbukas (clay drums) and homemade flutes, local singers would improvise songs about the hardships of life, while listeners would exhort them with shouts of “ya rai” (roughly, ”tell it like it is,” or “tell me about it!”). Slowly, the rougher qualities of rai were smoothed out, violins and guitars and accordions found their way into the music, and the grit and fire of the lyrics gave way to flowery words and sentiments (even as a more risqué form began to thrive underground in bars and backrooms and “whiskey parlors” based around the provocative and sexually charged performances of Cheikha Rimitti). By the fifties, the coming of television helped soften what was already a watered down sound, and, with the exception of Messaoud Bellemou (a trumpet player and bandleader who helped electrify and resurrect the spirit of the music) and a few others, rai had drifted into a musical and cultural dead end. “When I was young,” says Khaled, “rai wasn’t something that kids would listen to or relate to. It was for old men. They would go off in the evenings and leave their women at home and just sit somewhere with a bottle – and listen to rai. It was nightclub music, cabaret music.” Khaled was born Khaled Hadj Ibrahim on Leap Year, February 29, 1960 in Oran, Algeria, the son of a sometime policeman and his young wife. Fixated on music, by the age of 9 or 10, he had learned to play harmonica, bass, guitar, accordion and anything else he could get his hands on, playing traditional music, as well as imitating the pop music from the West that filled the streets and the airwaves. “We’d listen to The Beatles, James Brown, Johnny Hallyday, all sorts of dance music,” Khaled recalls.” No one knew what the words meant, but we’d imitate them anyway. I’d go up to my father and start singing “Sex Machine,” and he’d just be there smiling. He didn’t know what I was singing about. And actually I didn’t know what I was singing about! “We all tried to imitate James Dean, Johnny Hallyday, Gene Vincent, Elvis Presley, trying to find the right look, the right style. My uncle used to go to the barbershop and get what was called a Marlon Brando cut; you had to have a good “look” if you wanted to pick up girls.” Asked if there weren’t Algerian or Arab stars or role models, Khaled is momentarily puzzled, as if the idea itself were odd. ”No, no, no. We had singers, we had musicians, but THE LOOK, THE STYLE, that all came from over there,” he says, tilting his head toward an imagined America. In Oran, as a teenager in the 1970’s, Khaled began singing at weddings and was soon noticed and given a chance to cut a single. Released in 1974, when Khaled was 14, the song was a sensation. Despite the fact that it was ignored by radio and tv, it was heard all over the streets, in clubs and cabarets and blasting from tape stalls in the markets. “When we finished the record, the old guy who produced it asked what name I wanted to use; in our culture, entertainers always changed their names. I wanted my own name, so he said, right, you’re young, in Arabic that’s cheb, so we’ll call you Cheb Khaled.” From then on, virtually every artist working in rai has taken on the moniker of Cheb (Chebba for women), not only in emulation of Khaled, but in recognition of Algeria’s burgeoning youth culture. Most singers before were older and took on the title Cheikh or Cheikha, a mark of respect (like Master or Sir) but also of age and experience. The title “cheb” not only implied youth, but a certain pride and cockiness in being young, and it had a streetwise edge to it, like DJ or MC. Khaled’s music grew with his career, and as he electrified his sound, adding drum machines and synths’ and electric guitars, his tapes were labelled “PopRai” to differentiate them from the more traditional and acoustic music of the past. From a dark, spare sound, as raw and powerful as country blues, Khaled’s music grew into a dense electric sprawl, rich and entwined as the rhythms of P Funk or Prince, unbelievably soulful, yet always ethereal (based partly on the fact that unlike most Western funk and dance music that emphasizes the backbeat, the constant 2 and 4, rai puts its emphasis on the one, giving the music an emotional lift). The end result often sounds like reggae that’s been sped up and dragged through the casbah. “That’s Moroccan music you’re hearing, not reggae,” Khaled insists. “I’ve heard records made from before I was born of Gnawa music that has the same groove as reggae, the same root in the bass, the same rhythm you hear in Bob Marley.” Like Marley in reggae, Khaled has become the central, fixed point in the world of rai, the singer against whom every other singer is measured, the one who is defining the boundaries of the music and, in the process, the boundaries of Algerian culture. By the early’80’s, the “Pop Rai” tag was quietly dropped; Khaled’s success was so pervasive that when people talked about rai, 9 times out of 10 they were talking about him. For all the acclaim, money was never plentiful. Rai artists were treated much the way blues musicians were in the 30’s and 40’s in America; i.e., publishing and royalties for sales didn’t exist, and an artist was simply handed a wad of money (in Khaled’s case, usually about $2,000) for each album they recorded. That was all they’d ever earn for that record, and it led to artists re-recording the same songs (with slight variations) for as many labels as possible. “The people who put out my tapes all have diamond rings and beautiful cars, beautiful women, fine houses, so I know those tapes sold well,” Khaled shrugs. ”You can find tapes of mine all through the Arab world and all through Europe, but I don’t know numbers, I don’t really know how many are out there. Throughout the Arab world, music is sold on cassette, and popular cassettes are easily and frequently bootlegged. There are no pop charts, no Billboard top ten lists, and it’s convenient for everyone but the artist to be vague about sales figures. According to what passes for reliable information, Khaled sells upwards of 200,000 official copies of his releases and maybe another million or so in bootlegs in Algeria alone; given his popularity in North Africa and the Middle East, you should probably start multiplying, though whatever number you multiply by, Khaled was still left with the same flat fee of $2,000. To supplement his income, Khaled performed at weddings; smuggled cars and motorcycles into Algeria from Morocco; and started to seriously look West. “I first heard tapes of Khaled in the mid 80’s, and I flipped,” says Martin Meissonier. ”I went to Algeria to find him and see about making a record, but I found he already had two different “exclusive” contracts within Algeria alone; putting something together just wasn’t possible.” A year later, Meissonier finally got a chance to work with Khaled through the intervention of Safy Boutella, a wealthy young Algerian who had studied music at the Berklee School in Boston and who had government connections; and through Hocine Snoussi, a colonel in the Algerian army who was able to get Khaled a visa and who helped finance a state of the art album recorded in Paris. The record (Kutche) has a dedication to Colonel Snoussi, thanking him for “the greatness of his heart.” Future pressings may also want to mention the greatness of his bank account; Khaled has yet to receive any royalties from the album, probably his most popular and fully produced work up to now. “It was a trade,” sighs Djellali Ahmed Ourak, Khaled’s manager. ”Khaled never received a cent from that record, but he got his papers and his freedom. He’s been here for five years, and he hasn’t been back to Algeria since. At least,” he lowers his voice, “not officially.” Never having completed his military service, if he returns, Khaled would be subject to the draft, as well as to the wrath of the fundamentalists, not a cheery prospect in even the best of times. And these are not the best of times. “Ever since I was young, I’ve always said what I thought,” says Khaled. ”There’s no anger in it, it’s just who I am. The people who like me and my music love that about me, they know I tell the truth; at least my truth. But those who don’t like me get furious when they hear my songs because they’re about change, and change is dangerous to Islam. Islam doesn’t take well to change. ***

When the weather grows warmer, Khaled gives a free concert on the outskirts of Paris, near Mairie D’Ivry. Khaled and I drive down together, along with Khaled’s cousin, a hefty man with a thick black moustache who runs a nearby café.

“In Paris they stop me,” his cousin complains, shaking his head as a police car drives past. “They see an Arab in an expensive car and phhht… they pull me over. So I go out to L.A. and what happens? They still pull me over, only THERE they think I’m Mexican. And over there I WANT to look Arab. What do I do?” “Easy,” I explain. “Wear a turban and carry a bomb. Works every time.” Humor does not always translate well. Khaled and his cousin stare at me for a moment and then drive on in silence. “America,” Khaled says after a while, shaking his head. “America,” his cousin agrees. Fortunately, we get lost, which changes the subject. We think we’re looking for a concert hall and drive around in circles until a local points out the actual venue: a beautiful 16th century farmyard, enclosed by barns and fences, a stage set up just in front of a chicken coop filled with hens and ducks and turkeys and geese, all of whom stare warily at the throngs of young Algerians pouring into the yard, hoping they’re not hungry. Khaled and his band take the stage late in the afternoon, and even before they begin, the young Arab girls move up front and start to dance, moving to a still unheard pulse, getting ready, adjusting their rhythms to fit the beat as the music starts; closing their eyes, they lift their arms to just above their heads, their fingers weaving tiny patterns in the air, their hips moving at half the speed of their hands; and then the pattern is reversed and their hips are flying, their hands in slow motion. The men stand back a few paces, drinking beer, watching the women and trying halfheartedly to avoid being pulled into the ring. Dancing, the men seem shy and slightly demure, looking over at their friends as if asking for help, never quite sure what to do with their beers, where to put their feet, while the women luxuriate in the music, at one with the beat, until it seems as if the rhythm is actually coming from their hips, fed to the drummer and the darbuka player by a wild and invisible current. In the middle of a song, two young girls run onto the stage, and then three more, and then more still, until Khaled is surrounded by 16, 17, 18 of them, all embracing him and touching him. And, as the security guard stands momentarily baffled, Khaled simply throws his arms around as many as he can hold, delighted by the scene, carried away by the music, and by all the different pleasures of his life. The moon is just coming up, the air is still, and there is a faint smell of honeysuckle and of fresh baked bread. And lost in a sea of girls, surrounded on stage, Khaled simply throws his head back and laughs. ***

The Backstory of the Above:

I thought Cheb Khaled and the world of rai was a perfect story for the New York Times Magazine, and the editors at the Times agreed; but when we started to work out the logistics, they couldn’t decide whether it should be assigned through their music department or through politics/cultural affairs. “You can’t separate them,” I said. “Of course we can,” they explained, and that was that. So I talked to the powers that be at Rolling Stone. I had recently traveled to Senegal and written a long piece on Youssou N’dour for them, and it had won an ASCAP/Deems Taylor award, so they were gracious enough to give me an assignment to travel with Khaled throughout Europe along with a generous expense account. It was one thing for Khaled to find me backstage at various concerts around Paris, but now that I might actually be on the road with him, he was concerned about having an American along for the ride : would I get carsick, sing Abba tunes, both at the same time? Khaled took me for a drive, a way for us to get to know each other. We were in Marseilles, it was a lovely day, early October, at the start of the first Gulf War. We drove about two hours out of the city into a small Arab town and parked outside what turned out to be an Iraqi bar. He pushed me inside, not unkindly, but dramatically, and called out to the folks inside, “Hey! Meet my friend! The American!” And then he burst out laughing and ran outside. The room was dark, filled with smoke and sweat and cheap beer, and all the men inside looked like Bluto, from Popeye… dark, burning eyes; thick black beards down to here; stomachs out further; and they surrounded me. One of them pushed me up against the bar with his stomach and glared. “So…” he laughed. It was not a happy laugh, but dry, mirthless and raspy. He let that word hang there and waited for it to fade. “So….how you like George Booosh?” It was not a question. I seldom think well on my feet. And I seldom have to. I shook my head and looked at him. “So….” I asked, “how do you like Saddam?” We looked at each other. When Khaled returned, ten minutes later, he found us buying each other drinks. I traveled with Khaled for about 6 weeks. Rolling Stone loved the piece I wrote, and it was talked about as a cover story, though I found that pretty unlikely. But what I found even more unlikely was that they would cancel the story altogether. The Gulf War, the anti-Muslim sentiment that was in the air, and concern about alienating advertisers all combined to derail it. Antaeus, a wonderful literary magazine co-founded by Paul Bowles, ran it in their next issue, and it won an award as one of the stories of the year. But I wanted it to be more widely seen, mostly for Cheb Khaled, who deserved it. And more. Much more. - B.C. June 2022 To hear several phases of Khaled’s music: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DcgKD0q6jkM Chebba https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5BGG5IZLnQ Hada Raykoum https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CzIQr-VfVWM La Camel https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9548ltAmpno Nssi Nssi |